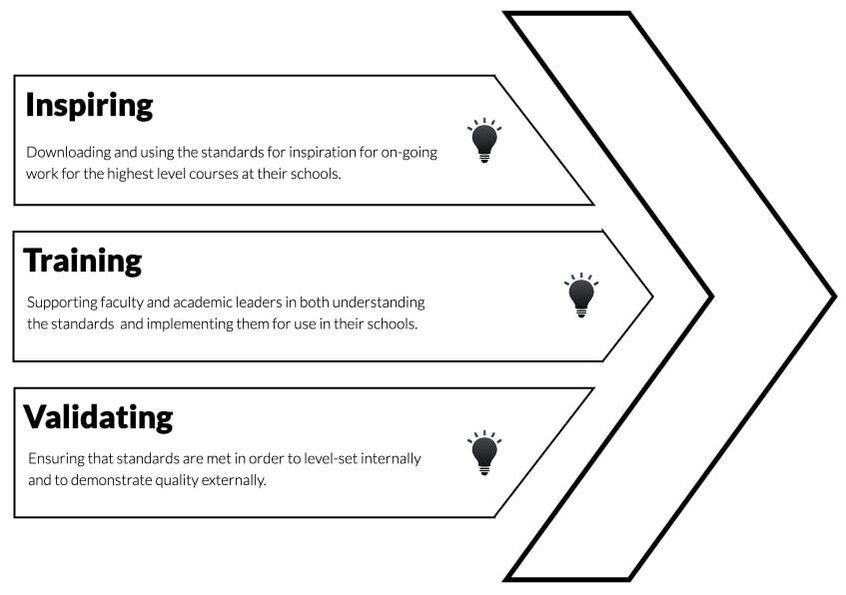

Three Ways Schools Might Use the Advanced Independent Curriculum™

Peter Gow

Peter Gow

Where Have You Been All My Life? Standards That Can Work For Schools & Kids

Say the words “standardized testing” to any student anywhere, and you will strike fear into a young heart.

Say the words “standards and accountability” to teachers anywhere, and you will strike fear into their hearts.

The S Words. Standardization and standards. But it didn’t have to be that way.

Whatever value what Nicholas Lemann has called The Big Test may have had for the urgent sorting of soldiers during World War I, a century and two pandemics later, universal standardized testing has been revealed as having been all along a tool for sustaining inequities. Its outsize role in American education also adds enormous stress to the lives of students and their teachers and families, whether in relation to college access or as a hammer for pounding out perceived unevenness in the quality of public education. In the latter role it has stunted the development of creative curriculum by teachers and been used as a tool not for the improvement but for the punishment of underfunded schools and hardworking teachers in poor communities that are “underperforming” by standardized measures—even knowing the palpable effects of systemic racism and economic inequality.

The Common Core Standards were an attempt to build universal accountability measures into the matrix of “school improvement.” In many cases, however, educators report that teaching to these can have a stultifying effect on creativity and student curiosity.

Beyond the Common Core you’d have to look pretty hard for a useful generalized body of published standards for learning. Some discipline-related professional organizations have developed their own content standards, like the American Council of Teachers of Foreign Language and the Next Generation Science Standards. But fully articulated and applied standards for learning at a single school, say, are kind of hard to come by.

I remember the first time I was at an independent school about to undergo regular accreditation and how surprised I was to learn that the process had essentially nothing to do evaluating course-by-course or grade-by-grade academic quality. In independent schools we have let outcomes speak for themselves, often citing standardized testing data as a proxy for “academic excellence” and trotting out college and next-school lists to further prove value. Of course, historically, independent schools have been bastions of just the kind of systematized inequity and white privilege that standardized testing has sustained. We’re all trying to do better, but we need new tools for creating the kinds of truly equitable “academic excellence” and “high standards” often touted by independent schools as their most desirable virtues.

In February of 1991 the late Grant Wiggins brought S Words together in an article titled “Standards, Not Standardization.” Educational Leadership’s subhead for the piece laid out the case: “Our schools must no longer accept token efforts judged by variable criteria. We must expect quality from every student based on models of outstanding performance.” We instinctively know and are made uncomfortable by the fact that idiosyncratic-by-teacher-or-department unwritten academic “standards” must often be sussed out by anxious students and lack consistency from class to class and teacher to teacher. Grant called us to account for this, as he and others led us in moving schools toward the use of understanding-based curriculum and assessment design. The school where I worked in the 1990s even bought a “Standards, Not Standardization” resource kit for helping our faculty adopt “backwards curriculum design.”

Even so, a continuing challenge has been the absence of articulated learning measures that aren’t either content-based or so prescriptive as to squelch individual teacher creativity or fail to meet real students in real schools where they are.

Independent schools have the great good fortune to have built-in tools for discovering, articulating, and developing their own standards. The process of exploring a school’s full curriculum often begins with a “Picture the Graduate”-type exercise that asks faculty to consider the student outcomes implied and even promised by the school’s various statements of mission and values. These ideals spell out the promise made by the school to students and families and ought to be our Pole Stars for designing academic programming.

But it has long been a challenge to help faculties and academic leaders translate these general foundational and aspirational statements into the language of real standards that can be used by teachers to create and deliver student learning experiences with consistent expectations for engagement and quality.

When the Independent Curriculum Group and One Schoolhouse came together in 2019, a new pathway presented itself: to merge the ICG’s long-standing clarion call for schools to use their missions and values as the basis for all they do and One Schoolhouse’s decade of experience designing and delivering courses to a set of rigorous and consistent standards that offer students from different schools across the world a reliably solid learning experience.

In our Standards for Advanced Independent Curriculum, One Schoolhouse provides a tool to help individual schools draw upon their own, specific missions and values to create high-level courses that serve up to their very own students high-quality, challenging, and meaningful learning experiences. At last, these standards offer schools a tool for bringing mission, values, and standards together and for documenting and continuously evaluating whether their promises are truly being kept in their classrooms.

Welcome, standards we can use! We’ve waited a long time for you!

Say the words “standardized testing” to any student anywhere, and you will strike fear into a young heart.

Say the words “standards and accountability” to teachers anywhere, and you will strike fear into their hearts.

The S Words. Standardization and standards. But it didn’t have to be that way.

Whatever value what Nicholas Lemann has called The Big Test may have had for the urgent sorting of soldiers during World War I, a century and two pandemics later, universal standardized testing has been revealed as having been all along a tool for sustaining inequities. Its outsize role in American education also adds enormous stress to the lives of students and their teachers and families, whether in relation to college access or as a hammer for pounding out perceived unevenness in the quality of public education. In the latter role it has stunted the development of creative curriculum by teachers and been used as a tool not for the improvement but for the punishment of underfunded schools and hardworking teachers in poor communities that are “underperforming” by standardized measures—even knowing the palpable effects of systemic racism and economic inequality.

The Common Core Standards were an attempt to build universal accountability measures into the matrix of “school improvement.” In many cases, however, educators report that teaching to these can have a stultifying effect on creativity and student curiosity.

Beyond the Common Core you’d have to look pretty hard for a useful generalized body of published standards for learning. Some discipline-related professional organizations have developed their own content standards, like the American Council of Teachers of Foreign Language and the Next Generation Science Standards. But fully articulated and applied standards for learning at a single school, say, are kind of hard to come by.

I remember the first time I was at an independent school about to undergo regular accreditation and how surprised I was to learn that the process had essentially nothing to do evaluating course-by-course or grade-by-grade academic quality. In independent schools we have let outcomes speak for themselves, often citing standardized testing data as a proxy for “academic excellence” and trotting out college and next-school lists to further prove value. Of course, historically, independent schools have been bastions of just the kind of systematized inequity and white privilege that standardized testing has sustained. We’re all trying to do better, but we need new tools for creating the kinds of truly equitable “academic excellence” and “high standards” often touted by independent schools as their most desirable virtues.

In February of 1991 the late Grant Wiggins brought S Words together in an article titled “Standards, Not Standardization.” Educational Leadership’s subhead for the piece laid out the case: “Our schools must no longer accept token efforts judged by variable criteria. We must expect quality from every student based on models of outstanding performance.” We instinctively know and are made uncomfortable by the fact that idiosyncratic-by-teacher-or-department unwritten academic “standards” must often be sussed out by anxious students and lack consistency from class to class and teacher to teacher. Grant called us to account for this, as he and others led us in moving schools toward the use of understanding-based curriculum and assessment design. The school where I worked in the 1990s even bought a “Standards, Not Standardization” resource kit for helping our faculty adopt “backwards curriculum design.”

Even so, a continuing challenge has been the absence of articulated learning measures that aren’t either content-based or so prescriptive as to squelch individual teacher creativity or fail to meet real students in real schools where they are.

Independent schools have the great good fortune to have built-in tools for discovering, articulating, and developing their own standards. The process of exploring a school’s full curriculum often begins with a “Picture the Graduate”-type exercise that asks faculty to consider the student outcomes implied and even promised by the school’s various statements of mission and values. These ideals spell out the promise made by the school to students and families and ought to be our Pole Stars for designing academic programming.

But it has long been a challenge to help faculties and academic leaders translate these general foundational and aspirational statements into the language of real standards that can be used by teachers to create and deliver student learning experiences with consistent expectations for engagement and quality.

When the Independent Curriculum Group and One Schoolhouse came together in 2019, a new pathway presented itself: to merge the ICG’s long-standing clarion call for schools to use their missions and values as the basis for all they do and One Schoolhouse’s decade of experience designing and delivering courses to a set of rigorous and consistent standards that offer students from different schools across the world a reliably solid learning experience.

In our Standards for Advanced Independent Curriculum, One Schoolhouse provides a tool to help individual schools draw upon their own, specific missions and values to create high-level courses that serve up to their very own students high-quality, challenging, and meaningful learning experiences. At last, these standards offer schools a tool for bringing mission, values, and standards together and for documenting and continuously evaluating whether their promises are truly being kept in their classrooms.

Welcome, standards we can use! We’ve waited a long time for you!